There are some watchmakers you just know go back to the early days of horology. You know the type, those with a penchant for ornate guilloche and perpetual calendars, maybe a cheeky minute repeater here and there. And yet some of the most important names in the field aren’t the ones that hold on to that centuries-old legacy of hand-crafted fine timepieces. In fact, you could argue the opposite. We’re talking about names like Rado, the ‘Master of Materials’ and here’s a look at their history.

The watch industry at large is one that doesn’t change often – more in incremental nudges than seismic shifts – but it does change and Rado has, since 1917, been a vital part of that change. Yes, Rado. From an outside perspective, they might seem like an odd brand to have very directly shaped certain aspects of watchmaking but in a very real sense, their mission statement has pushed design and materials further than other brands would have. That mission statement? “If we can imagine it, we can make it. And if we can make it, will!”

Rado was officially launched in 1950, but the company was initially founded in 1917, in Lengnau.

It’s a very Swiss statement of course and one that’s not exactly humble. It’s basically saying, ‘we can do anything’, but in 1917, Rado – or the manufacturer that would become Rado – was a very different animal. Founded by the brothers Fritz, Ernst and Werner Schlup (feel free to say it a few times to get it out of your system now), who converted their parent’s home into an atelier in the Swiss village of Lengnau. If you can’t wait for your kids to move out, imagine how the Schlups felt.

The earliest known advert featuring the Rado name (1929).

Rather than your waster of a son just waiting to make it big on YouTube however, the brothers actually had a knack for business. Perhaps it was the team effort, perhaps it was growing military demand, perhaps it was their innate Swiss quality, but the Schlup’s manufacturer grew at a staggering rate until, by the end of World War II, they were among the largest in the country. This of course meant it was time to capitalise on that success with a name: Rado.

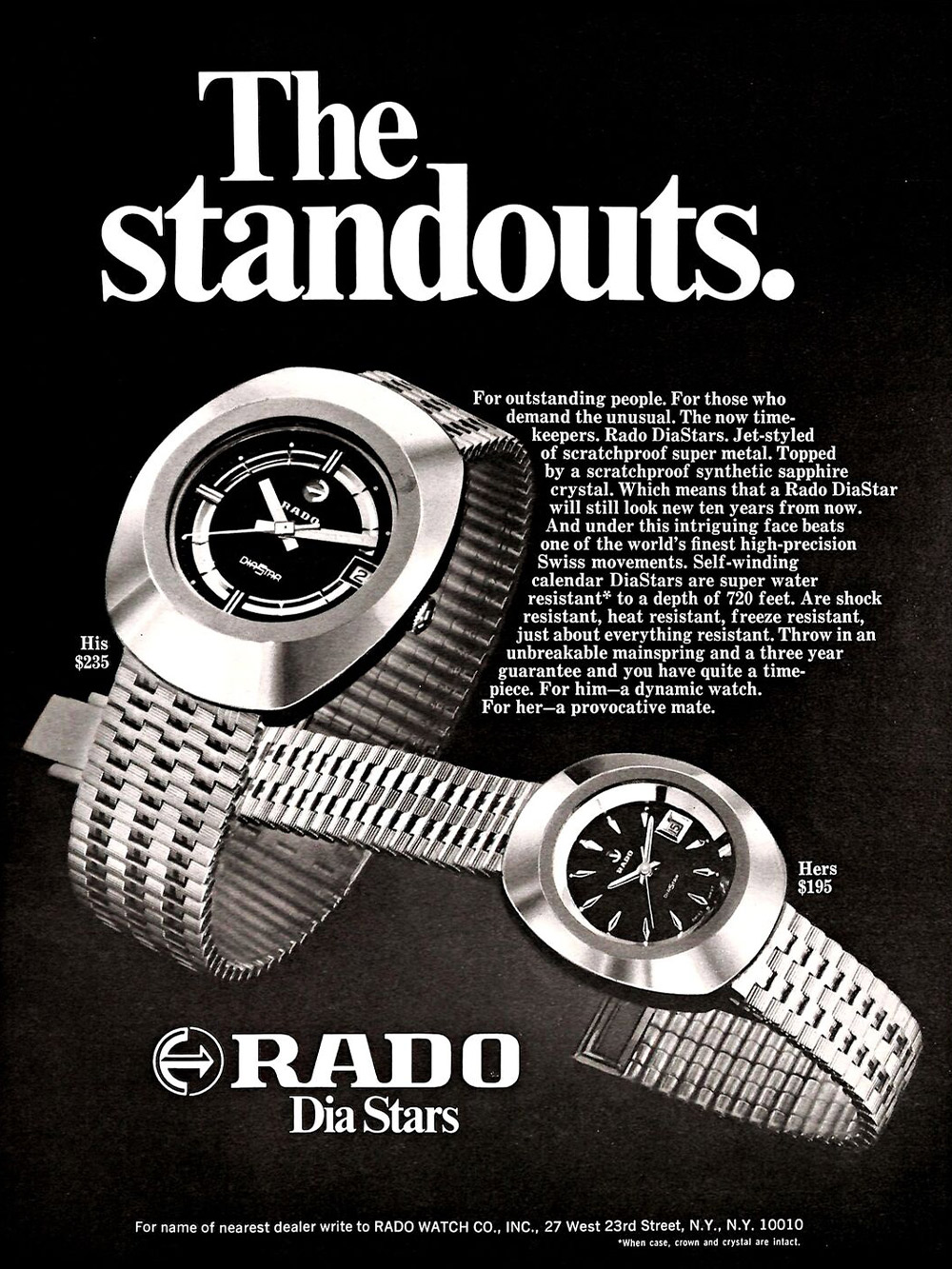

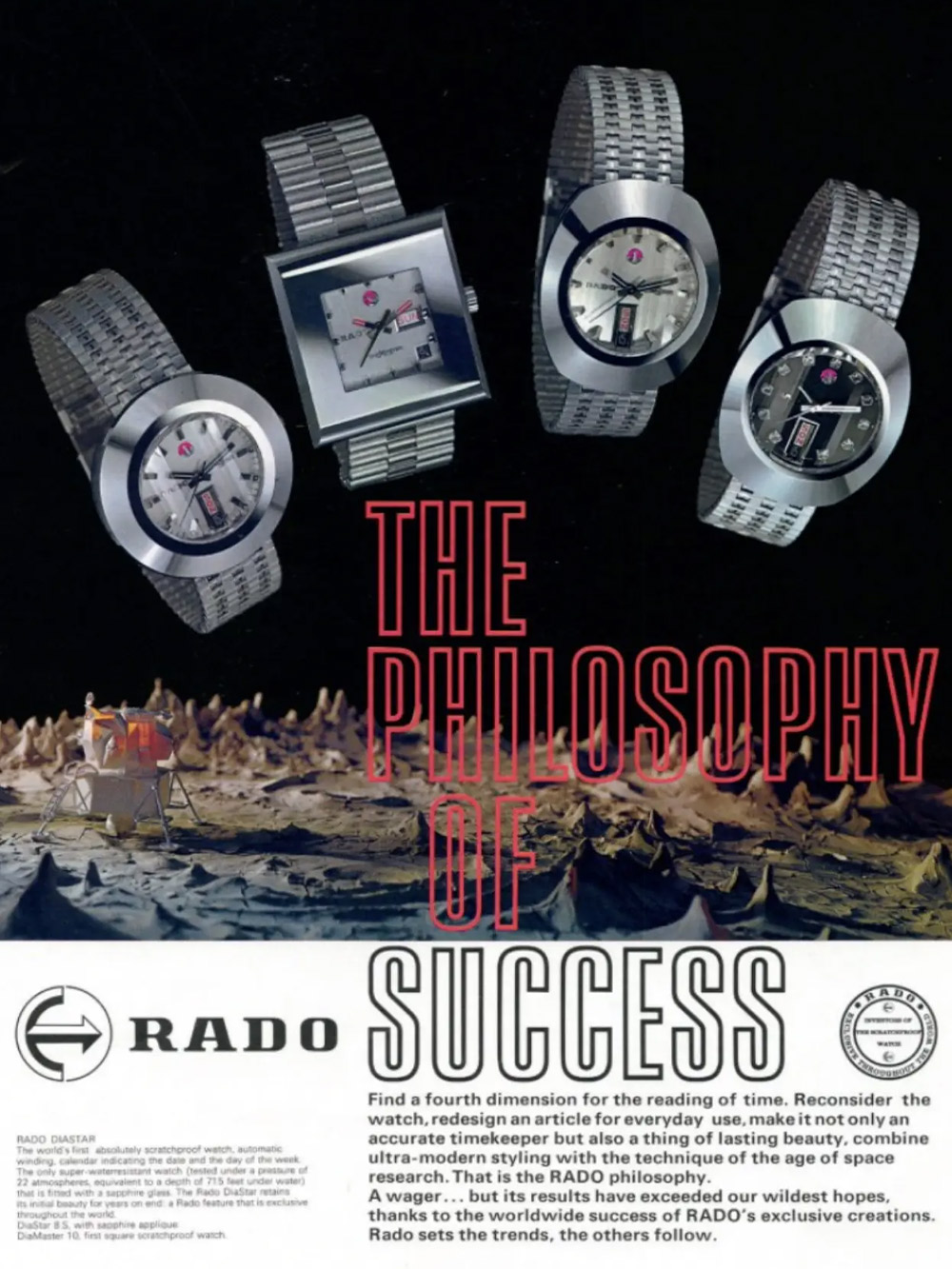

Rado Diastar adverts from the 1960s

This is about the time their famous motto came in and honestly, by this point the brothers Schlup had earned it. Not only did they have their new brand – Esperanto for ‘wheel’, in case you were wondering – but they had their first watch to go with it, the Rado Golden Horse, swiftly followed by the Green Horse, both of which had the now iconic moving anchor logo and ‘sign of life’ indicator.

The horses did well, thanks to a combination of solid design and promotion of their water resistance, but the real lightbulb moment came a little later with one of the most influential watches of the 1960s, the Rado DiaStar 1.

The original Rado DiaStar from 1962

The 1962 release was everything other watches were not. It pioneered a hard metal case designed to put the middle finger up to any potential scratch risks. That alone was a seriously impressive leap forwards when basic steel and gold were the only otherwise visible options, but it was combined with a rounded design that looks futuristic, even today. Indeed, while the Captain Cook might be Rado’s most famous reference today (a watch that was, incidentally, released the same year), the DiaStar was the genuine innovation that established the watchmaker’s reputation as the ‘Master of Materials’.

It is worth going into precisely what that hard metal case is. Often the Diastar is cited as being the first ceramic watch. Sorry, I should say incorrectly cited. The material in question was actually tungsten carbide, a ceramic/metal alloy. The ‘pure’ ceramic we mostly see today is zirconium oxide and is a different thing entirely. The first for that would have been IWC’s Da Vinci, over 20 years later. Indeed, tungsten carbide is still a cutting-edge material today; it’s the only reason Bulgari can create a 1.7mm watch that actually works. There’s an argument (a small one, but still) that they wouldn’t have gotten there without Rado.

Rado Anatom (1983)

Over the next decade, Rado doubled down on two things: diving watches with the ever-expanding Captain Cook, and unique shapes that would give Cartier a run for their substantial money. Collections like the 1975 Elegance and ‘76 Glissière were sharp, angular and had that same retro-futurism as the Diastar – including dabbling in the at-the-time innovation of quartz.

The modern Rado Anatom 40th Anniversary

Speaking of quartz, it was at the end of the ‘70s, beginning of the ‘80s that the quartz crisis hit the watch industry. Hard. Manufacturers were shuttered as they just couldn’t compete with the uber-accurate, battery-powered movements ushered in by Seiko and others. Rado on the other hand, were doing relatively well, especially when, in 1983, they launched the Anatom.

The Anatom not only had a name befitting the atomic age, but its cylindrical sapphire crystal was the first of its kind. It was smooth, curved and fit itself to the wrist more comfortably than anything that had come before. ‘Ergonomics’ were less of a thing in the ‘80s than they are now, except when it came to the Anatom.

Andy Warhol Rado Painting on display in the Halcyon Gallery (1987)

It was a success, and you don’t need to take my word for it: legendary pop artist and watch aficionado Andy Warhol (whose collection included fabulously shaped Cartiers and Piagets) dedicated a 1×1 metre painting to the Rado. It was one of the last works he ever produced.

Rado’s distinctive high-tech ceramic cases before being sent to assembly and control.

So, shape was very much Rado’s area of expertise, but this is the ‘Master of Materials’ and, other than a funky sapphire, they’d not pushed too hard in that direction. That’s why 1986 saw the Integral and its use of high-tech ceramic. Unlike the DiaStar, this was true ceramic and while IWC beat them to the punch, the Integral was much more accessible and much more in-keeping with the minimalist aesthetic that would come to define later era Rado.

There were other materials toyed with, too. 2002’s Rado V10K was made from a form of diamond, with a hardness of 10,000 Vickers (hence the name) and 2011’s R5.5 was offered in Ceramos, a more advanced combination of metal and ceramic. The modern era of Rado however really kicked off with the introduction of colour in the True Thinline Collection, designed in association with Le Corbusier. That and, of course, the reintroduction of the Captain Cook.

Rado Captain Cook High-Tech Ceramic x England Cricket

Which brings us to Rado’s latest release and our cover star for this issue: the Captain Cook High-Tech Ceramic x England Cricket. The name says it all, really. It’s a Captain Cook, so you have serious dive watch credentials; it’s in high-tech ceramic, so it’s hard as nails and much more scratch resistant, and it’s a tribute to the England Cricket team.

In-keeping with latter-day Rado’s penchant for colour, that means a handsome combination of blue ceramic case and white ceramic bezel. While I doubt any players particularly want to take to the field with a dive watch on their wrists, they most definitely could.

Coloured ceramic isn’t just hard; it’s hard to produce. There’s a reason it took until now for it to become a ‘thing’, instead of just black or white. As ceramic maestros don’t really know the final colour before the material is fired and potentially wasted, there’s a lot of going back to the drawing board. Being able to perfectly match it to the Cricket uniform is no mean feat.

Inside is the latest generation Rado movement, the R808 automatic with an 80-hour power reserve, backing the 43mm wide, hard outer case with chronometric performance that you might actually want to see through the sapphire dial. It’s one of the best encapsulations of what modern Rado watch is: cool, colourful and ceramic. Though with 150 of them available and a worryingly good price tag of £4,200, you might only see these on the England team’s wrists.

More details at Rado.

It’s a beautiful time time piece elegant low key for the discriminate people in the know will know it.Stunning design excellent movement and accurate.

My late father owned a beautiful Rado Diastar which was stolen when he was assassinated at a price in 1986. I am saving to get an exact brand- A Rado Diastar is my watch of choice

Rado is best watch I like very much

A B C D E F G H